Current Research in Emergency Medicine

[ ISSN : 2832-5699 ]

COVID-19: An Emerging Etiology for the Brugada Pattern on EKG

1Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, USA

2Baptist Health Boca Raton Regional Hospital, Boca Raton, Florida, USA

Corresponding Authors

Keywords

Abstract

Brugada syndrome is an inherited arrhythmogenic disorder characterized by autosomal dominant mutations in several identified genes encoding for cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels. The underlying mutations predispose individuals to ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death. Oftentimes, the condition is asymptomatic until a triggering event occurs, with sodium channel blockers, fever and alcohol being common risk factors for appearance of the Brugada pattern on EKG. COVID-19 diagnosis can also present a risk for Brugada presentation. COVID-19 is known to exacerbate other cardiac arrhythmias and channelopathies such as Long-QT syndrome, in addition to being known to cause fever and electrolyte imbalance. We present the case of a patient exhibiting the Brugada pattern on EKG with symptoms of chest tightness, shortness of breath, and tachycardia shortly after testing positive for COVID-19 in the Emergency Department. Due to the potential for unmasking the Brugada pattern as well as other cardiac arrhythmias during COVID-19 infection, patient and family history should be thoroughly considered to rule out potential genetic conditions when examining patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2. This case is presented to highlight COVID-19 as a potential etiology of the Brugada pattern on EKG in genetically predisposed individuals.

Introduction

Brugada syndrome is an inherited arrhythmogenic disorder characterized by autosomal dominant mutations in several identified genes with about 50% of cases carrying loss of function mutations in the SCN5A and SCN10A genes which encode for cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels [1-4]. When loss of function occurs in these genes, there is a weakened sodium current in conjunction with an unchanged potassium current. This may lead to complications including ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and eventually progressing to sudden cardiac death in some cases [1]. The Brugada pattern manifests on an EKG as coved ST-elevation with an accentuated J-wave [5]. The pattern can precede episodes of ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The mutations described above predispose individuals to sudden cardiac death, though patients are typically asymptomatic prior to an event that ‘unmasks’ their condition. Risk factors for symptomatic events include fever, alcohol use, sodium channel blockers, and inflammatory responses [1,6,7]. Additionally, there is some evidence COVID-19 is a risk factor for Brugada unmasking in genetically predisposed individuals. COVID-19 is a known risk factor for other cardiac arrhythmias and channelopathies and can trigger additional cardiovascular pathologies such as long QT-syndrome [4,8-12]. COVID-19 symptoms also include several confounding risk factors for Brugada presentation including fever, diarrhea and associated electrolyte imbalance. Fever has been shown to decrease cardiac sodium channel capacity, exacerbating existing deficits seen in patients with sodium channel mutations associated with Brugada [8,13]. As a result, there is significant concern for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who have a genetic predisposition to Brugada syndrome. We present the case of a patient exhibiting the Brugada pattern on EKG with symptoms of chest tightness, shortness of breath, and tachycardia shortly after testing positive for COVID-19 in the Emergency Department (ED). This case is presented to offer insight into the emerging risk for COVID-19 associated Brugada presentation.

Case Presentation

Case Report

A 61-year-old man with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes, DVT, pulmonary embolism, and CVA presented to the ED after two days of worsening subjective fever, chest tightness and shortness of breath. The patient tested positive for COVID-19 on admission to the ED, reporting multiple instances of vomiting and diarrhea. The patient has a history of palpitations and presyncope, with episodes of light-headedness and dizziness occurring when he is working as a painter but more recently occurring at rest as well. He had no prior EKGs indicating potential cardiac arrhythmias or ectopic foci. The patient has a family history of cardiomyopathy (father), fatal myocardial infarction (mother), and unknown conditions requiring all of his siblings to have pacemaker or ICD implantation. No further medical or family history was made available at time of admission.

Physical Examination

The patient was alert and oriented upon arrival, appeared well nourished and in no acute distress. Upon admission, the patient was afebrile (36.8o C), had a blood pressure of 107/58 and an oxygen saturation of 97%. Skin examination showed three healing abdominal wall incisions from a recent laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Cardiac exam showed tachycardia (105-112 beats per minute) with a normal rhythm and no murmur or gallop. Peripheral pulses were present and capillary refill was normal.

Laboratory results, Imaging, and EKG

Laboratory results are insignificant barring a troponin that is slightly elevated (Table 1).

Table 1: Laboratory results

|

Laboratory test |

Patient Values |

Reference Range |

|

WBC |

6,700 cells/mm3 |

4,500-11,000 cells/mm3 |

|

Hemoglobin |

16.5 g/dL |

14-18 g/dL |

|

Hematocrit |

50.10% |

42-50% |

|

MCHC |

32.9 g/dL |

33-37 g/dL |

|

Sodium |

135 mmol/L |

136-142 mmol/L |

|

Glucose |

149 mg/dL |

70-140 mg/dL |

|

Monocytes |

19% |

2-8% |

|

Absolute Monocyte Count |

1.27x10^3/mcL |

2-8x10^2/mcL |

|

Troponin 1 |

<0.015ng/mL |

0-0.04 ng/mL |

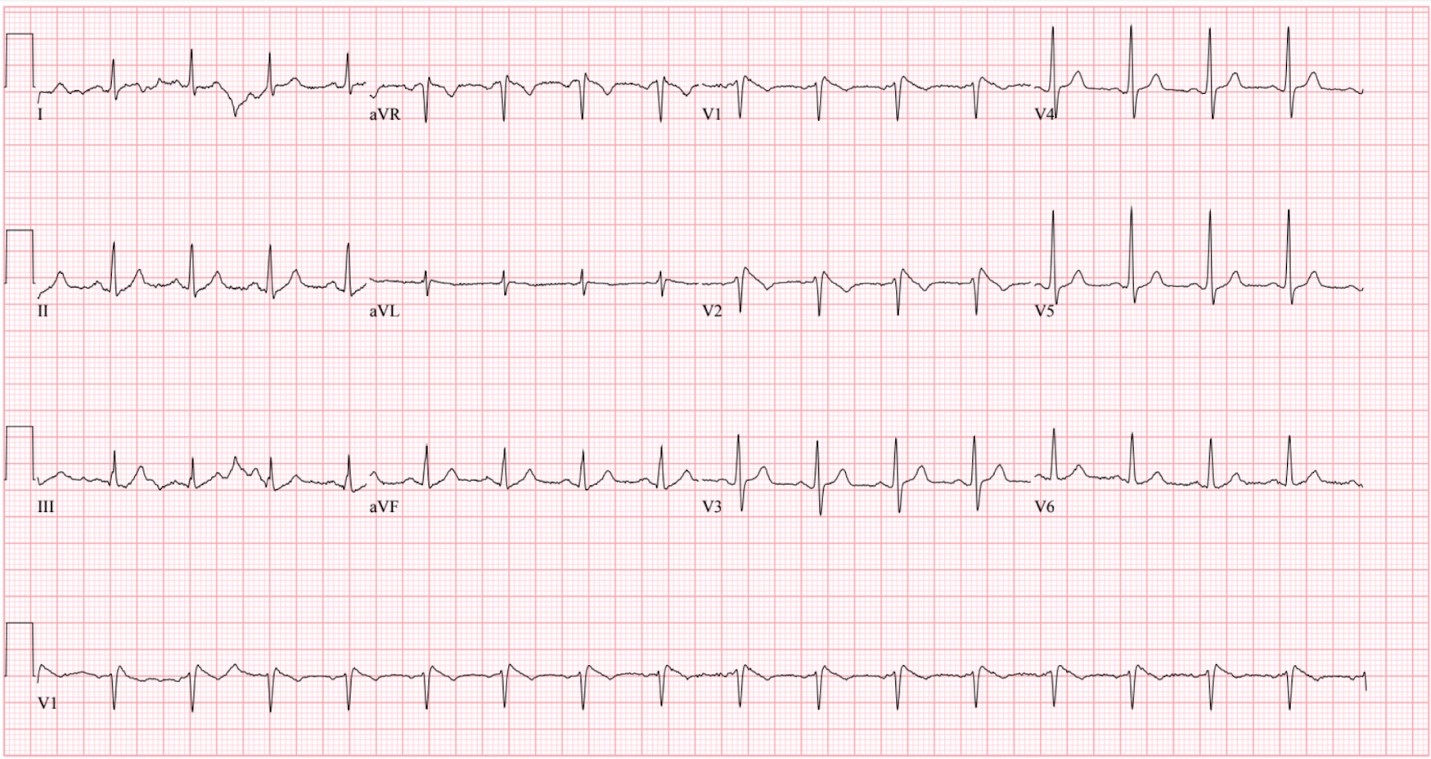

CT-Angiogram with contrast found no evidence of pulmonary embolism, aneurysmal dilation, or dissection. Heart size was normal. A chest x-ray showed no acute cardiopulmonary process with normal pulmonary vascularity and cardiac silhouette. The initial EKG revealed a coved ST elevation in V1-V2 indicative of Type 1 Brugada pattern (Figure 1). At the time of the EKG, the patient was experiencing tachycardia, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

Figure 1: Type-1 Brugada pattern

Figure 1: Type-1 Brugada pattern

Diagnosis and treatment

Based on the evidence of the clinical findings, past medical history, family medical history, and EKG results, the patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 infection preceding Type-1 Brugada pattern. The patient was given subcutaneous enoxaparin daily and received acetaminophen for COVID-19 symptoms. He was monitored via telemetry until COVID-19 symptoms availed. The patient was recommended for follow-up and ICD placement due to his risk factors for sudden cardiac death. The patient was also advised to follow up with genetic testing.

Discussion

Brugada syndrome is a dangerous condition for patients, as many are asymptomatic before experiencing severe symptoms such as ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. Brugada syndrome accounts for almost 50% of sudden deaths in patients without structural heart defects and is the leading cause of death in South Asia for men under 50 years of age [14]. There are many risk factors identified for Brugada presentation, but COVID-19 is an emerging concern particularly for patients with a personal or family history of Brugada syndrome. A worldwide survey of COVID-19 patients found that 18.27% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients had an arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation and atrioventricular block upon presentation to the hospital [15]. Several factors may play into this incidence, including fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and the associated immune response. In addition to its flu-like symptoms, COVID-19 has shown to have an arrhythmogenic impact in asymptomatic patients, indicating risk beyond associated symptoms. Due to the prevalence of arrhythmia and other cardiac instances in COVID-19 cases, patient and family history should be thoroughly considered to rule out genetic conditions in patients with cardiac symptoms. Early identification of Brugada syndrome allows for thorough risk assessment and adjustment of treatment protocols, with a focus on telemetry monitoring.

Our patient presented to the emergency department with a positive COVID-19 test, tachycardia, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. His EKG showed a Type 1 Brugada pattern, which was later confirmed in the context of his history of presyncope and family cardiac history. Our patient is unique in that he presented to the ED without the main known triggers for Brugada presentation– at the time of his EKG he was afebrile, did not report frequent alcohol use, and was not taking medications that are known to exacerbate the condition. His lack of known risk factors for presentation highlights the impact of COVID-19 on this instance of Brugada presentation.

Patients with Brugada syndrome, or risk factors for Brugada syndrome, concurrent with COVID-19 diagnosis require extensive monitoring throughout hospital admission. In Brugada patients, the sodium gated ion channels function at a reduced efficiency and increased temperature further diminishes sodium channel capacity– exacerbating the condition [8,13]. As a result, reducing and controlling fever in COVID-19 patients with the Brugada syndrome or associated risk factors is vital to preventing complications of Brugada pattern on EKG. For patients diagnosed with COVID-19 inducing the Type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG, risk factor management is key– reducing fever, electrolyte imbalance, and avoiding medications that can exacerbate cardiac symptoms. We present this case to bring clinical awareness to the risk that COVID-19 has on unmasking the Brugada pattern on EKG in patients with significant past medical and/or family history.

Conclusion

In patients diagnosed with COVID-19 inducing the Type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG, risk factor management is key– reducing fever, electrolyte imbalance, and avoiding medications that can exacerbate cardiac symptoms. We present this case to bring clinical awareness to the risk that COVID-19 has on unmasking the Brugada pattern on EKG in patients with significant past medical and/or family history.

Conflicts of interest

None

Funding

None

References

- Zimmermann P, Aberer F, Braun M, Sourij H, Moser O (2022) The Arrhythmogenic Face of COVID-19: Brugada ECG Pattern in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 9(4): 96.

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, Carlo Pappone, Bella PD et al. (2002) Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation 105(11): 1342-1347.

- Hu D, Barajas-Martínez H, Pfeiffer R, Dezi F, Pfeiffer J, et al. (2014) Mutations in SCN10A are responsible for a large fraction of cases of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 64(1): 66-79.

- Chang D, Saleh M, Garcia-Bengo Y, Choi E, Epstein L, et al. (2020) COVID-19 Infection Unmasking Brugada Syndrome. HeartRhythm Case Rep 6(5): 237-240.

- Gourraud JB, Barc J, Thollet A, Le Marec H, Probst V (2017) Brugada syndrome: Diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 110(3): 188-195.

- Gussak I, Antzelevitch C, Bjerregaard P, Towbin JA, Chaitman BR (1999) The Brugada syndrome: clinical, electrophysiologic and genetic aspects. J Am Coll Cardiol 33(1): 5-15.

- Roterberg G, El-Battrawy I, Veith M, Liebe V, Ansari U et al. (2020) Arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome patients induced by fever. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 25(3): e12723.

- Adedeji OM, Falk Z, Tracy CM, Batarseh A (2021) Brugada pattern in an afebrile patient with acute COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 14: e242632.

- Wu CI, Postema PG, Arbelo E, Behr ER, Bezzina CR, et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm 17(9): 1456-1462.

- Tsimploulis A, Rashba EJ, Rahman T, Almasry IO, Singh A, (2020) Medication unmasked Brugada syndrome and cardiac arrest in a COVID-19 patient. HeartRhythm Case Rep 6(9): 554-557.

- Vidovich MI (2020) Transient Brugada-Like Electrocardiographic Pattern in a Patient With COVID-19. JACC Case Rep 2(9): 1245-1249.

- Lugenbiel P, Roth L, Seiz M, Zeier M, Katus HA, et.al. (2020) The arrhythmogenic face of COVID-19: Brugada ECG pattern during acute infection. European Heart Journal Case Rep 4: 1-2.

- Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, Vatta M, Nesterenko DV, et al. (1999) Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res 85: 803-809.

- Brugada P, Brugada R, Brugada J (2000) The Brugada syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep 2: 507-514.

Citation: Tharp M, Knopp BW and Parmar J (2022) COVID-19: An emerging etiology for the Brugada pattern on EKG. Curr Res Emerg Med 2: 1039